Washington D.C. was the last place I wanted to move. I have brought that up many times over the years, but I think it’s important now that I’m leaving to remember that the love I feel for D.C. was hard-won.

In October 2021, I moved into a basement unit in Adams Morgan, taking over a lease for a journalist couple who wanted a condo. My room had a small window and the previous renters’ dog had scratched up the door frame. It was at this time that I was in the absolute pits of pandemic-induced OCD and just didn’t want to leave the house at all. I was scared of everything, didn’t know anyone, and I didn’t want to be in D.C.

Slowly, and I mean slowly, I started to explore my neighborhood, one block at a time. When I moved, I knew there was a music venue that closed by me and a record shop. At the time, I had started collecting CDs again in pandemic boredom, so one day I walked over to the store to see what they had — Smash! Records. Unbeknownst to me, Smash! is a semi-historic hub for old punk shit, Vans sneakers, and constant Dischord distribution, but I quickly figured that out. I remember my first time in there, scoping the CD shelves, snorting at their frankly ridiculously priced T-shirt collection, and flipping through their old copies of Thrasher. The whole place felt handmade and haphazard with thick coats of pink paint and friendly signs saying that the tiny Prince standee wasn’t for sale, so stop asking. I loved it immediately. I think I went every weekend for months.

Quickly, I decided that every time I went to Smash! I wanted to buy something cool and D.C.-ish. because I begrudgingly wanted to understand the city around me. That fall, I started researching everything about D.C. music. I began with the big names: Bad Brains, Fugazi, Minor Threat, etc. and the emo stuff I knew: Rites of Spring and Embrace and from there I found Fire Party, Jawbox, The Nation of Ulysses, Beefeater, Government Issue, S.O.A, and a million other bands. I read books about early riot grrrl and watched documentaries about harDCore and how they both came into fruition under D.C.’s unique proximity to political power. I started to really feel D.C. in everything I read and watched and, most importantly, listened to.

I have this vivid memory, one that kind of permeates the miserable sludge of my 2021, where I am drinking a very expensive and bad mocha from a very expensive and bad coffee shop, but listening to “Repeater” by Fugazi over and over again. It was really cold and I remember my cracked knuckles bleeding (from months of OCD overwashing), but I kept lapping the block because I wanted to keep listening to Fugazi. I was so annoyed and overheating but it was the first moment since I moved where I felt like I could really breathe.

So, now, four years later, D.C. punk music and its history became a private passion of mine. I say private not like it’s a secret, it’s just something I really fell in love with by myself. And as a result of this love, I have gone to tons of talks, documentary screenings, and shows for the sake of better understanding an era I missed and to hear good ass music. I’ve seen Alec Mackaye play and I’ve seen J. Robbins play and I’ve seen Brendan Canty and Joe Lally play together. I saw Velocity Girl reunite. I’ve seen Ted Leo three times, twice at Black Cat. I got the gossip on Dave Grohl building a replica of the Atlantis. I have heard conversations where people talk about “Kathleen” and by that they mean Hanna. I have heard conversations where people talk about “Henry” and by that they mean Rollins. I got the full story on the Black Flag Häagen-Dazs shirt from Ian Mackaye. I’ve seen Ian Mackaye at shows. I’ve heard Ian Mackaye at talks. I’ve watched documentaries with Ian Mackaye. I’ve met Ian Mackaye.

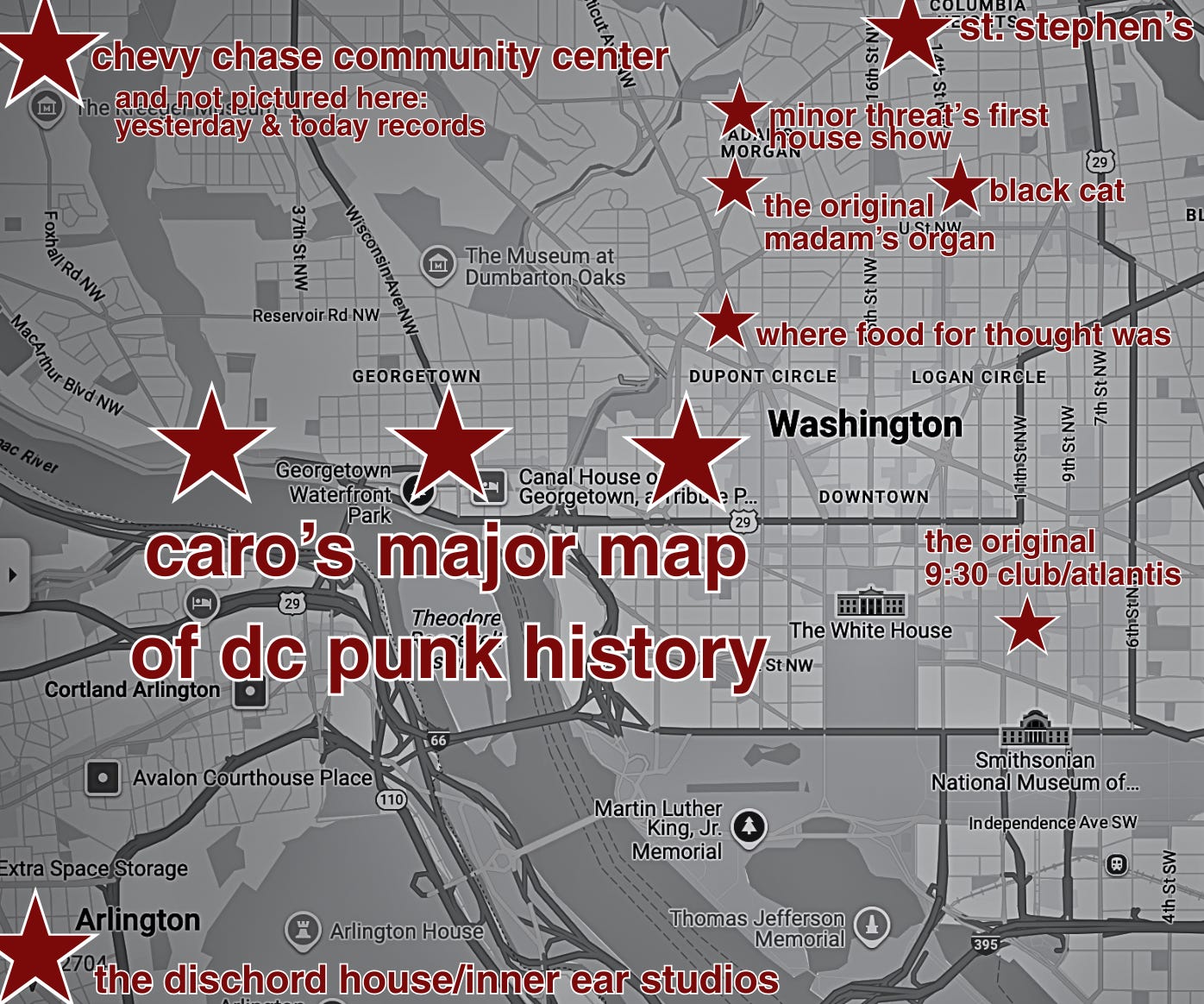

And now I’m moving. When you move from somewhere like D.C., you get a lot of questions about if there’s anything you want to check out before you leave. I think when people asked that, they were mostly referring to the Air and Space Museum, but I’ve already seen that. So I made my own list of stuff I wanted to check out, something to put actual places to the stories I’ve heard:

I pitched this a mini road trip to my friends, Bailey and Rook, while I was waiting out a thunderstorm a couple weeks ago and because they are awesome, they said yes. So on Sunday July 20th, we piled in Rook’s car and started driving to Maryland. The following includes pictures from Bailey.

Stop One: The House Where Minor Threat Played Their First Show

I am not sure how accurate this is, but it was my entryway into realizing how integral my neighborhood, Adams Morgan, was to the development of D.C. punk shit. I was watching a random harDCore documentary with my roommate and someone was telling a story about seeing Minor Threat’s first show at some house — 1929 Calvert Street. My roommate and I both turned to each other with the same question, “Isn’t that in Adams Morgan?” Sure enough, it is. We found it the next day. It’s truly just a nice tall row home that looks like the homes around it and I’m sure Minor Threat played there because someone’s parents lived in the house and said yes to their kid having a party. But as simplistic as it probably is, something pretty monumental happened in that basement. It sold for like $1.1 million last year.

We actually accidentally drove past it on this trip. Whatever, I’ve pointed it out before to my friends. It’s my favorite place to point out.

Actual Stop One: Yesterday & Today Records

We spent the drive over to Y&T shittalking your band. Yes, you.

That’s a joke. I don’t think the losers I shittalked follow my Substack. But we bitched and moaned about the lackadaisical state DIY music is in and the fact that a lot of people are way too fucking lax about difficult things. Hard to make inclusive music when some artists make uncomfortable environments on purpose. Anyway, we wove through a lot of greenery and down baby cliffs and ended up in a very regular parking lot.

Yesterday & Today Records was buried in one of many strip malls in Rockville, Maryland — a good 30 minutes from what I would consider the center of D.C. punk stuff. It’s not there anymore. It closed in 2001, long before I ever got to D.C. and back when Fugazi was still playing shows, but its impact is still everywhere. The store was opened in 1977 by Skip Groff, an affable punk music obsessive, and his shop quickly became a center for all things DMV sound. Groff sold local albums, touring bands did signings, and basically every punk musician worked there at some point (most notably: ¾ of Fugazi, half of Youth Brigade, half of Velocity Girl, the list goes on). However, perhaps the most important thing Groff contributed to this whole thing was running Limp Records. On his label, he both produced and released D.C. bands’ albums — you might have heard about some of them: Bad Brains and a Minor Threat (the list goes on). Before there was Dischord and Smash!, there was Limp Records and Yesterday & Today and I am in the parking lot of that hallowed ground.

The building sits on the end corner of the strip, encased by windows of the parking lot view. It’s really plain and now it’s a Duck Donuts. Obviously, we dropped in for donuts and coffee.

I didn’t expect anything magic when I walked in, the place hadn’t been Y&T for 24 years, but it was obviously not supposed to be a donut shop. It was too cavernous and the counter was built awkwardly into the back. You can easily imagine the crates. This road trip was going to be a lot of that: imagining what a building once was. Back to the car.

Note: We drove by a Torchy’s Tacos and then pretty immediately whipped the car around for lunch. Once we got back into the car again, full of tacos, we were off to stop two.

Stop Two: The Chevy Chase Community Center

This wasn’t a big stop or anything. I actually wasn’t even sure I had the right place — also someone tried to hack my Venmo during this stop. However, I think it’s right and will continue writing this like I’m right. The Chevy Chase Community Center is what I kind of think of as the birthplace of emo music.

In 1985, D.C. bands held Revolution Summer. It’s a fairly mythic-feeling summer of action that re-centered the music scene’s politics, creative Positive Force DC, and legitimately oversaw the creation of emo music via Guy Picciotto and his new band Rites of Spring. While RoS had kicked it at a couple shows, it was at the Chevy Chase Community Center on June 14, 1985 that a movement was started. Every first hand account of the show remembers the grip Picciotto’s set held them all in and how his words and passion inspired the fervor for the rest of the summer. Blah blah blah Real Emo copypasta etc. But this is very real to the memory of music in D.C. It’s very tangible. And it all happened in a big brick building in downtown Chevy Chase.

Again. No magic happened while I looked at the building, if anything I was struck by how normal it was. How a regular community building birthed a movement by accident. The community center doesn’t host shows anymore or at least I don’t think it’s really been asked to host shows (correct me if I’m wrong).

We talked about Revolution Summer in the car. This past month, a couple people held documentary screenings for the 40th anniversary. The screenings were all pretty small but cool documentaries and the events were well attended. These throwback events are always well attended. D.C. music is obsessed with its own mythology and I mean that positively. In fact, I think it’s vital. If D.C. isn’t constantly reviewing and reaffirming their impact on punk music, who else will? Why doesn’t D.C. do that still?

I firmly believe that D.C. has the best music scene in the country right now, but we’re not in a place where 40 years from now we’ll be having screenings of fan documentaries. And it's a total shame. D.C. music is innovative and loud and clever and fun. If I could leave any thoughts to anyone in D.C. who reads this, fucking own it. Write a manifesto, start that label, print that zine, and for the love of God — get on that stage.

Stop Three: The Dischord House

This was the big one. Obviously. The house is probably the most important building in the Washington D.C. area.

First. I think it’s pretty funny that D.C.’s most locally prideful dudes lived in Arlington, VA. That’s the only joke I have though. I don’t think this is just a crucial D.C. monument. I think the Dischord House is one of the most important places in music history. The albums that were worked on here are some of the best rock records ever made and the bands that lived here are equally important. But more than that, the Dischord ethos is something I believe in like nothing else.

I don’t tour, I don’t make music; it doesn’t matter what I think on this topic, but their true blue “we’ll do it ourselves” attitude and the code of ethics that accompanied it is endlessly admirable to me. It seems so ahead of their time that the the Dischord guys believed so heavily in accessible music distribution, but that’s just what they thought was necessary: distributing cheap CDs around the country to making the music downloadable when the Internet Age actualized to uploading the whole catalog to Bandcamp for streaming (with emphasis on only buying on Bandcamp Fridays). I also like how that all materialized into Fugazi later, a band of action and commitments.

In all the D.C. documentaries I’ve watched, it's always emphasized that these musicians weren’t trying to make marketable things or make their own market, they were just so compelled to do something and say something that music was the only option. They also always bring up how everything was inspired by their community. For example: Ian Mackaye’s job at Yesterday & Today and his proximity to Skip Groff and Limp Records made record label management real to him and Jeff Nelson. Their lives in the ever-toiling politics of living in D.C. made them politically outspoken in a way that was naturally built into their label, their lives in a struggling city made them desperate for action and affordability.

So there we were. Standing on the sidewalk outside of all this. The house was a darker maroon than I thought, the gate was rusted, and the yard was overgrown. I was trying to match the porch steps with The Picture and I never noticed the windows at the top.

Honestly, it felt kind of forgotten. Just an old house on a street of old houses and next to a beat-up 7/11. And I think that’s right. Nothing about Dischord says they want to have a shiny perfect building to operate out of. It’s kind of silly to care about. It’s just a house.

But it really isn’t. Back in 2023, I saw 7Seconds do a little show at Black Cat with One Step Closer and Gumm. I remember checking Gumm’s Instagram while walking over and seeing that they had visited the house and met Ian. They took a picture on the steps and Ian came to their set. It’s just all important.

We all took turns getting individual pictures and hiked back into the car.

Stop Four: Inner Ear Studios

Just about seven minutes from the Dischord House is Inner Ear Studios, the legendary space where Don Zientara recorded some of my favorite albums: Fugazi’s Repeater, Fugazi’s Steady Diet of Nothing, Fugazi’s In on the Kill Taker, Fugazi’s Red Medicine, Fugazi’s End Hits, Fugazi’s The Argument, and Braid’s Frame & Canvas.

I said all that like Inner Ear Studios is still there — it’s not. In fact, all that’s left is a wall and a lot of demolition accoutrement. It’s really weird honestly, just this knocked-down building surrounded by a dog park and across the street from the historic Weenie Beenie. Someone in the car pointed out that a lot of the bands we love probably dropped by the Weenie Beenie before recording. I wondered if Chris Richards and Harris Klahr had hot dog breath when they recorded No Kill No Beep Beep.

Luckily, that hasn’t stopped Zientara. Before Inner Ear Studios, Zientara recorded from his basement, a house somewhere on S. Oakland St. also in Arlington, and that’s where he is again. I went to a talk held at the D.C. public library last year to see him talk with Ian Mackaye. They were supposed to talk about The Inner Ear of Don Zientara: A Half Century of Recording in One of America’s Most Innovative Studios, through the Voices of Musicians, but these things always turn into a couple guys shooting the shit. Zientara and Mackaye regaled infamous moments in the studio, named bands that only existed for three months, and recreated the sound of Scream fighting each other with the mic still in hand. But in between that, Zientara talked about his approach to recording. He described the process as ephemeral, which I remember thinking was really cool. I’ve never stepped foot in a studio space but I agree with the idea that you lose texture with elongated studio stays. I look for rawness in music and I find it in his recordings. Similar but different, I have a quote saved from him that “if [recording] becomes too serious, it gets too sacred.” He was, of course, sitting next to Mr. Too Serious, when he said that and it got some laughs, but was a really eye-opening thought for me. The best D.C. punk music captures a tangible humanness — it's loud and abrasive, and I never thought about how that came from one guy keeping it all in line. These weren’t bands concerned with perfect takes and perfect albums, they were concerned with getting it done, preserving it, and sharing it. There’s an urgency and a built in informality that gives D.C. it’s particular sound. Sessions were done when Don Zientara said they were.

Also apparently they were done when his water heater and furnace would get so loud they couldn’t record anymore.

We drove past the Pentagon to get back into D.C. kind of an irritating reminder of the conditions that made D.C. music so powerful.

Stop Five: Food For Thought (now Bistrot du Coin)

Finally back in D.C. for the last couple stops, starting with the site of Food For Thought. My understanding is that after the closure of Madam’s Organ (I’ll get to that) the D.C. punks of the 80s needed a new spot to play shows. Then someone did the unthinkable — they asked their parents if they could help. Enter Bob Ferrando, who owned a swanky restaurant called Food For Thought in Dupont Circle and his son, Dante Ferrando, who played drums in Gray Matter.

In 1999, the Washington Post called Food For Thought “the Hippies’ Last Resort” and from what I can tell, that’s pretty apt. Food For Thought was a cheap, casual restaurant that opened its doors in the chaos of 1970s D.C. and served a lot of vegetarian meals. They catered to a vast group of Dupont regulars like “hippies, gays, lesbians, neo-hippies” and hosted community gatherings. One old employee explained it like this — “People were always asking me, ‘Are you going to the march?' and I would say, No, I'm going to be feeding the marchers.’” Eventually, Food started hosting shows and that was that. It was the perfect place for Dante and his wayward friends to play their loud music.

Food For Thought formally closed its Dupont location in 1999, leaving behind an unremarkable building in the hub of Dupont Circle. It’s now where the Bistrot du Coin sits and when we drove by on Sunday, the restaurant was busy but boring.

Luckily, it took more than jacked up rent (from $900 to $9000 in 26 years) to stop Ferrando and his vegetarian meals. Food For Thought re-opened as part of his son Dante’s nightclub: Black Cat. Until 2019, Food For Thought Café operated with Black Cat, closing when Dante made the difficult decision to size down the club (closing Food and two auxiliary stages) on the ever-changing 14th Street strip. In old interviews I’ve read, this decision was necessary but sucked, harsh proof of a real loss of punk culture in the city and almost as importantly, the real loss of a beloved hang.

In 2018, Dante Ferrando did two things: he blamed the city’s indoor smoking bans and online dating for ruining vibes and told The Washington Post that “he wants to be clear that the Black Cat’s new moves are not a retreat, nor the beginnings of some long goodbye. It’s strategy. It’s survival.” If I’m being optimistic, this flexibility from the Ferrando family has been crucial for keeping music pumping through the city. And the good news is that Black Cat has somewhat brought back Red Room, just on the second floor now, for smaller local gigs.

Don Zientara once said something about how D.C. starts its own movements and own music and sound because it’s left to its own devices and I think Food For Thought’s transition into Black Cat and Black Cat’s continued defiance on 14th Street, now catty-corner from a Trader Joe’s and next to a Madewell Men’s, really captures that.

Stop Six: St. Stephens

I actually found out about St. Stephens before I moved to D.C. Back in 2019, Dan Ozzi posted a video of a harDCore band called No Justice’s first song in their final set. The video is from 2000 and an absolute riot from start to finish where about half the room charges the stage while the front man pitches one of the cymbals into the crowd before disappearing. This iconic performance takes place in the basement of St. Stephens.

Everyone has been to St. Stephens in one way or another in this car. I never went to a show there, I meant to but it never worked out, but I always dropped by their annual punk flea market. Usually that stuff is embarrassing as fuck but this was a legitimately good one.

I am a CD collector, as I noted at the top, and this was always the most fun day for CD stuff because people would just sell anything. Good old Dischord releases, neatly organized stuff from CD books, and my favorite: random CDs that have been sitting in the seller's parents’ basement for years. It’s in these hallowed halls that I got a hold of tons of demos from tons of bands that existed in the early Internet age. One has their parents’ phone number scrawled on the corner, another has a hand drawn cover (pencil sketch not quite erased), and another has an AOL email address printed and glued on the side. It was also here I also got a hold of a copy of the Visualizing the History of Fugazi fanzine (which you should check out) That’s the kind of group the St. Stephens flea draws and I’ll bravely vouch for them.

I will say, there’s one group that operates here sometimes that I regret, truly regret, not getting involved with: Positive Force DC. PFDC is an activist collective that started 40 years ago in Revolution Summer. They created a lot of protests and music and zines but also organized a lot of community outreach like delivering groceries to the elderly and volunteering in food banks. Having a group like PFDC helped make the ‘80s and ‘90s bands that I value for their outspokenness activists in the first place. Like every show, Fugazi played in D.C. was a benefit, and they played a lot of shows. PFDC created a culture of not just speaking up when you had a microphone, but creating tangible change with every show. That is really cool. That makes this music so real to me.

I looked at St. Stephens longer. It’s just an Episcopal Church. It’s kind of in Mount Pleasant, kind of not in Mount Pleasant but it has always kept its doors open for even the rowdiest of shows. We drove by it pretty quickly — Bailey and Rook trying to remember who they saw here. My mom works at an Episcopal Church, so I like it. The sun was low in the sky at that point. One more stop.

Stop Seven: The Original Madam’s Organ

Many people who know me know that I’m a regular at a dive-bar-flavored cocktail bar in Adams Morgan called Grand Duchess. I kick around there most nights and have had 100 Miller High Lifes sitting at the bar stools. I’m there right now as I write this.

A couple weeks ago, I was at a documentary screening for Punk the Capital and there was a really long segment on a storied punk house called Madam’s Organ (as I mentioned in the Food section). The house was actually a kind of art house and while the burnout stoner artists didn’t like punk, they believed that music should be allowed to be played, and let the bands perform in the gross walls of the house. The documentary had footage of plenty of gigs, including the only known recording of The Enzymes (the film’s volume is actually turned up louder for their clip, which was also the longest in the movie), and talked about Bad Brains living there. The whole deal only lasted about a year before the punk kids got tired of the old hippies’ bullshit (there’s a mild chance that straight edge exists just because Teen Idles in particular was so fed up with the residents of that house).

What does that have to do with my local hang? Well, I’ve never really cared about where the place was. I assumed it was demolished with health code stuff, but in the documentary, Alec Mackaye threw out the address: 2318 18th St. NW. That’s the building across the street from my bar. I’ve walked by it countless times, no clue that it was, at least to me, a historic monument. It’s a dispensary now (the hippies won).

NOTE FOR D.C. READERS: Yes, there’s a Madam’s Organ on 18th Street — it’s a bluegrass bar that totally sucks and has like an unreasonable cover for sucking so hard. I have confirmed that it is unaffiliated with the original spot.

On Sunday, this is where Rook dropped me off. I wanted to stop by Grand Duchess and say hey to a friend who was working there, but I made them drop me off outside the old Madam’s Organ building so I could look at it in the context of everything I had seen that day. I just really love it. I don’t know.

And that concludes our tour and I am really sad to leave. As I type this I’m sitting with a pile of Dischord CDs I got at Smash! and a spritz Grand Duchess.

I don’t think I’m ready to put all my feelings about D.C. in writing yet, that’s another post for another week (next week) but I will say this. I hope Athens, Georgia is ready because I’ll start this all over again. Starting with Weaver D’s Delicious Fine Foods.